Netanel Miles-Yépez

Photo by Netanel Miles-Yépez from the Día de los Muertos exhibit at the Longmont Museum, 2014.

When I was 18, I had an extraordinary dream. In the dream, I saw my grandfather sitting in a chair at a dining room table. Seated in front of him was my aunt feeding him his meal, carefully lifting each bite to his mouth. My grandfather was already an old man in his 80s when I knew him, and he lived with my aunt who took care of him; so there was not much out of the ordinary in this, except that he was never so feeble as to require feeding. What was extraordinary was that his face and hands were those of a skeleton. He was dressed like my grandfather, and even had his wavy mass of silver hair and his horn-rimmed glasses, but they sat on a living skull, whose boney jaw opened to receive the food, and even appeared to chew it as I watched!

But still more extraordinary was the fact that, at that time, I was almost totally unaware of and had no sense of the significance of this kind of imagery in Mexican culture. Though I am from a Mexican-American family, and may have seen such imagery while visiting Mexico as a child, I knew nothing of its connection to the family-oriented traditions of the Day of the Dead, or to the fact that we make offerings of food on this holiday, effectively, feeding the dead.

"Ajedrez/Chess" (Oil on Canvas, 2009) by Netanel Miles-Yépez. In this depiction of the dream, the author's grandfather is being a fed his queen by his daughter, the author's mother.

Was it somehow written in my DNA, or something percolating up from the Collective Unconscious? I really don’t know. What I do know is that this dream had a powerful impact on me, making the Day of the Dead an important motif in my artwork, a significant aspect of my spiritual life, and ultimately, a symbolic form of continuity with my ancestors and departed family.

Today, as our Hispanic population continues to grow, the Day of the Dead and its imagery is becoming more visible in the United States. It is also becoming more popular among many young Americans, who seem to have embraced it as a kind of transgressive challenge to conventional society and our collective fear of death. But what is the Day of the Dead really about? And what is the meaning of its unusual and sometimes unnerving imagery?

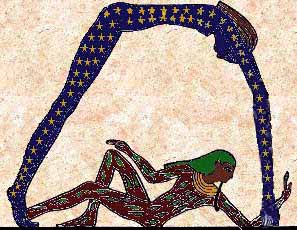

In Mexican culture, El Día de los Muertos, ‘the Day of the Dead,’ is a creative fusion of long-held indigenous beliefs and a Catholic Christian accommodation of them. Among the Aztecs, prior to the Spanish conquest of Mexico, death was governed by the Lord and Lady of the Dead in Mictlan, the Aztec underworld. The Queen of the Dead, Mictlancihuatl (Mikt-lan-see-watl), was seen as the caretaker of bones and the guide of spirits in the underworld. She was depicted by the Aztecs as a fleshless woman, a skeletal figure with an open jaw “to swallow the stars in the daytime.” In order for the dead to be accepted into Mictlan, offerings were made to the Lady of the Dead. Likewise, in her honor, the Aztecs held a month-long festival of the dead, which occurred in the ninth month of the Aztec calendar, sometime around the beginning of August. Though the Catholic Church obviously tried to suppress such customs and beliefs, they were never entirely successful in Mexico. And today, we see echoes of the Lady of the Dead reemerging in the popular Catrina imagery of Mexico, and more seriously in the growing Santa Muerte veneration there.

The Lady of the Dead in Mictlan, the Aztec underworld, Mictlancihuatl (Mikt-lan-see-watl). Image from "Mictlán: el lugar de los muertos" by Luz Espinosa.

Responding to the persistence of similar indigenous traditions among the laity in Europe, Catholic Christianity had already begun to accommodate such beliefs in the medieval period, fixing three special days in the Fall to change the focus back to a more acceptably Christian context. These days are: All Saints’ Eve (October 31st), All Saints’ Day (November 1st), and All Souls’ Day (November 2nd).

The first, of course, is well known in Western secular culture as Halloween, a word derived from All Hallows’ Evening. This day had originally achieved significance because the liturgical celebration of All Saints’ actually begins during the evening service the day before, on October 31st. All Saints’ Day is the day to officially remember and celebrate the holy example of all the saints of the Christian Church. Whereas, All Souls’ Day, the day after, is to remember and pray for all the “faithful departed.” However, what was officially sanctioned and intended by the Church was often quite different from how these days were conceived in the hearts of the people generally, especially where local custom and folk belief were maintained.

Mixing pre-existing indigenous beliefs and customs with the Catholic tridu’um, or ‘three-day observance,’ Mexicans (and other Latin American peoples) created their own unique celebrations for honoring the dead. For Mexicans, these three days have become the Days of the Dead, Los Días de los Muertos. According to folk-belief in Mexico, the Days of the Dead actually begin sometime in early to mid-October. For this is the time, it is said, when the dead begin their long pilgrimage back to the world of the living, an idea that has some resonance with the journeys the dead were thought to take in Aztec belief. Thus, the three days which are usually thought of as the Days of the Dead are really just the time of their arrival in our world. Apparently, during this season, and these particular days—perhaps being at the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter—the veil between this world and the next world is thinner, and thus, it is easier for us to be in contact with the dead.

Image from the blogpost, "When Death Delights: Dia De Los Muertos, Part 1" by deadwrite

For the most part, October 31st is the time of final preparations for the arrival of the dead. November 1st is called, Día de los Inocentes (‘Day of the Innocents’), or Día de los Angelitos (‘Day of the Little Angels’), being the day of greeting those who died as children and infants. November 2nd, then, is Día de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead, proper. (It seems that children run faster than adults, and thus arrive the day before, and I suppose, get to stay longer that way!)

Though customs vary from region-to-region, town-to-town, and family-to-family, it is common for Mexicans to go to the cemetery during these days to wash the stones and decorate them. We do this with flowers (traditionally marigolds), candles and incense, pictures of our loved-ones, mementos or objects associated with them, as well as food and drink they loved in their lifetime—all to draw and guide them back to us.

Often, this ritual takes on a festive atmosphere, as many families gather in the graveyard, playing and dancing to music loved by the departed, and telling stories of them—especially comic stories and anecdotes about their personal quirks—the things only we knew about them, the things that marked them as ours, and that only we, their family, can tell in the right spirit. Moreover, it is believed that the dead do not want us to be somber on this day, or to morn them. Rather, they would have us celebrate their lives and memories, for they are actually still alive . . . only on another plane of reality. Thus, on the Day of the Dead, we joke with and about them, just as we did in life! Often, these fiestas in the cemetery go on through the night, for the time with the dead is precious, and thus many people keep it as a vigil.

Image from blogpost, "Día de Muertos – Cozying up with Death in the Great White North" by SURVIVOR@37

But the holiday is also observed in one’s home; for many Mexican families will also construct elaborate home altars called ofrendas, or ‘offerings,’ containing food and other items in honor of their loved-ones. Although the ofrenda may look like a religious altar for worship, it is actually a kind of spiritual memorial and a place of communion. It is the focal-point in our homes for ‘greeting’ our returned loved-ones. Thus, nearby, is sometimes a basin of water and a towel with which they can refresh themselves after their long journey. On the altar are photos and marigolds, pictures of saints and other religious imagery, as well as el pan de los muertos (‘the bread of the dead,’ sweet pastries in the shape of bones), calaveras de azucar (ornately decorated sugar skulls), salt and something for them to drink. If they enjoyed cigarettes, or tequila in their lifetime—like my abuelita, my ‘little grandmother’— you might also find that on the altar. The altar is not too sacred for such items. It is meant to be warm and inviting.

While we, as their families, may certainly enjoy our ofrendas, they are truly for the dead. They are the symbol of our continued communion with them. It is said that the dead consume the ‘spiritual substance’ of the objects and the food on the ofrendas, sharing the material substance with us. By displaying their pictures, we remind them that we have not forgotten them. By making these offerings in love, we demonstrate to them that they are still present in our hearts, and we ask them to continue their presence in our lives. We ask them to guide us through the difficulties of life with their other-worldly vision, and to intercede for us from the other side.

Photo by Netanel Miles-Yépez from the Día de los Muertos exhibit at the Longmont Museum, 2014.

For this reason, a family will often have a more permanent, if somewhat less elaborate altar or ofrenda, year-round. For the dead are, according to Mexican belief, always with us. We remember them daily, speak to them when we need to, and even celebrate their death-anniversaries. (A kind of ‘birthday in heaven!’) This was something I learned very early when my abuelita, my grandmother, first taught me to say my prayers. She would put me to bed at night, and we would pray for my mother, my brother, my aunts and uncles, and each of my many cousins. But when we had finished praying for the living, we would then pray for the dead . . . for her mother and father, for her brothers and sisters, for my grandfather “in heaven,” and for my cousin who had been murdered. Somehow, it felt as if we were fulfilling a holy purpose with these prayers, giving something necessary to the souls of the dead, and I believe I slept more peacefully because of it.

It was not until I was older that I realized that most of the people I knew did not pray for their dead. The dead were just dead to them, or in a kind of heaven where they did not need our prayers, or in a hell where our prayers could not help them. But my grandmother’s heaven was not a place out of reach, not a place where the dead had nothing to do with us. Her heaven was a place of souls, where our ancestors and loved-ones dwelt together, a place where we could continue to speak to them, to offer them our love, and ask their help when we needed it.

You see, among many Mexicans and Latin-Americans, there is a sense that—la familia es sagrado—‘the family is sacred.’ That is not to say our families are perfect. They’re not. Nor are all Mexican families close. And yet, the sacredness of family is an ideal enshrined in our hearts, and which runs thick in our blood. We might fight amongst ourselves, but God help an outsider who dares to criticize a family member in our presence! I think it is because we know the difference between love and liking. Family is about love, and love is eternal. Liking passes from moment to moment. Sometimes I like you, sometimes I don’t. It depends on your behavior. But love is not so fickle. It’s what lies beneath, and fills the cracks between liking and dislike. It is what survives arguments and troubles. So we don’t confuse love with liking. We love our families—even when we don’t like them. And because family is about love, there are also people in our lives who become family—friends, partners, and spouses who enter into la familia, passing beyond the more ephemeral bonds of liking. We remember both on the Day of the Dead. And because la familia es sagrado, they stay in our lives, holy and inviolable, present both in our memories, and, in actuality, even after they have passed to the other side.

Photo by Netanel Miles-Yépez of the small ofrenda in the kitchen of his home, 2014.

Nevertheless, we treat their continued presence in our lives, playfully, with boney and ironic depictions of them. Sometimes, non-Latinos are puzzled and disturbed by the pervasive calaveras, the decorative ‘skulls,’ and the calacas, the skeletal figures associated with the Day of the Dead. This is likely because these images represent something very different in European culture than they do in Latin America. Death, certainly, but not as something negative. In European culture, death imagery is often sinister, something to scare us on Halloween or in horror movies, or else it is associated with a morbid nature or an edgy, counter-cultural fixation and embrace of things which seem unacceptable to the culture at large. As the Mexican poet, Octavio Paz put it: “The word death is not pronounced in New York, in Paris, in London, because it burns the lips. The Mexican, in contrast, is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it; it is one of his favorite toys and his most steadfast love. True, there is perhaps as much fear in his attitude as in that of others, but at least death is not hidden away; he looks at it face to face with impatience, disdain or irony.”[1] This is the feeling that pervades the Day of the Dead. It may not be absent of fear, but it does not run from it either. It embraces it, laughs at it, accepts it.

This awareness and acknowledgement of death in Mexican art and symbol is also used to bring some sense of balance to our lives. We see this in the everyday calacas, the skeletal art found throughout Mexico. A couple of examples:

An engraving of partying calacas by José Guadalupe Posada

Among the most common expressions of death imagery in Mexican or Latino culture are the often comical dioramas and figurines placing skeletal figures in recognizable clothing and contexts that create a comic or absurd impression. These range from stand-alone figures, like Catrina dressed as a grande dame or skeletal mariachis (musicians) or soldaderos (soldiers), to scenes of drinking parties, musicians at play, and people at other amusements —playing tennis or even in bed together (as I saw once in Mexico a few years ago)!

To most people, these figures and scenes are merely comical, if somewhat incomprehensible, curiosities. People enjoy them, but are rarely aware of what they actually represent. These figurines and scenes are typically Mexican object lessons, full of ironic humor, saying, memento mori (Latin for ‘remember death’). For, as another Latin proverb says, media vita in morte sumus, ‘In the midst of life we are in death.’ As we carry on, forgetful in our vain and often self-destructive amusements, death is always waiting for us, the one certainty. Thus, we are given humorous cautionary tales in these figures and dioramas, as if to say, “Go ahead, have your fun! But remember, you are really just drinking and dancing bones waiting for the graveyard!”

Some of the most famous illustrated calavera imagery comes from José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), a Mexican printmaker and political satirist of the late 19th and early 20th century. Posada's best-known works are of skeletal figures wearing various costumes, such as the Calavera de la Catrina, a vain and ridiculously dressed grande dame meant to satirize the extravagant life of the upper classes of that period in Mexico, who seemed to worship fashion and everything French. These depictions were meant to point out the ridiculousness of such pretentions to Mexican peasants who aspired to such dandi-ish dress and behavior. Posada’s Catrina, was later picked up and used by Diego Rivera in his mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alemeda Central, and, in time, was drawn into public Day of the Dead celebrations, assuming an altogether different stature as the Lady of the Dead (perhaps echoing Mictlancihuatl, which is perhaps natural, given the ever-present undercurrents of Lady Death in indigenous Mexico).

A detail from Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alemeda Central (mural, 1947) by Diego Rivera. Rivera is pictured as a little boy on the bottom left, with his wife, Frida Kahlo, above him, holding a yin and yang symbol.

In the end, we come back to this basic fact: “Fear,” as Octavio Paz writes, “makes us turn our backs on death, and by refusing to contemplate it we shut ourselves off from life, which is a totality that includes it.”[2] When the Mexican or Latino says, La Vida—‘Life’—they mean something more than life as opposed to death, but life and death together! Life, with a capital L, is the totality that contains both. “Nuestra muerte ilumina nuestra vida.” “Our deaths illuminate our lives.”[3] Thus, El Día de los Muertos is amongst the most holy, and the most human of all our holidays. We are reminded of how precious is life, and how sacred our relationships with the people we love most. And not least, we are reminded of how death cannot steal our joy if we embrace it and keep the connection to the dead.

* Netanel Miles-Yépez is a poet, artist, and Sufi spiritual teacher residing in Boulder, Colorado. This article is based on a talk delivered at the Lafayette Public Library, October 12th, 2014.

[1] Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude, trans. Lysander Kemp, Yara Milos, and Rachel Phillips Belash (New York: Grove Press, 1985): 57-58.

[2] Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude (1985): 79. In Spanish, "El miedo nos hace volver el rostro, darle la espalda a la muerte. Y al negarnos a contemplarla, nos cerramos fatalmente a la vida, que es una totalidad que la lleva en si." Octavio Paz, El Laberinto de la soledad y otras obras (New York: Penguin Books, 1997): 83.

[3] Paz, El Laberinto de la soledad y otras obras (1997): 75. Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude (1985): 54.